The Dutch adventures of Keith Haring

Longread — Jan 15, 2018 — Chris Reinewald

"You feel the deal is real You’re a New York City boy So young, so run into New York City/ New York City boy you’ll never have a bored day ‘cause you’re a New York City boy"

When he comes to Amsterdam for his first museum solo in the spring of 1986, the American artist Keith Haring (27) doesn’t spend all his time at the Stedelijk – he goes out, to into the city. Haring, a former art school student, began by making chalk drawings on empty advertising signs in the New York subway. His drawings were seen and appreciated, and even collected. Teenagers adore him. Haring’s vibrant bouncy figures are a perfect match with hip-hop street culture. So, when Wim Beeren (58), appointed director of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam in 1985, stages a major show of Haring’s work, it turns out to be a good move.

After his European debut in Rotterdam (1982), Haring becomes an overnight sensation following an exhibition at Tony Shafrazi in New York, later that year. By showing Haring’s work, Beeren brings youth street culture into the Stedelijk. Things were very different under the directorate of his predecessor, Edy de Wilde. Haring achieves his much-coveted museum status, but loses none of his street credibility. He won’t compromise – for anyone or anything.

Outside and inside the Stedelijk, Haring spray-paints a velum, a woven canopy that filters daylight, and creates an equally monumental wall painting using paintbrush and ink. With the help of a hydraulic platform, he energetically paints a mural on the exterior of the Stedelijk’s storage depot at the Markthallen. Keith’s a social being who lives to share his work with everyone. During the Kunstkijkuren at the Stedelijk, he makes a large wall drawing in the museum with a class of 12-year-old kids from Amsterdam. Relaxed, open, no airs and graces. But in the mid-eighties, a global economic crisis strikes, and causes a rift between the established and alternative art scene. Up to then, artists who sell poorly, or are just starting to develop their career, have been entitled to social benefits. But now, the Dutch government brings the scheme to an end. And people are angry.

In this climate of austerity, Dutch art critics have little sympathy for the Haring exhibition. They accuse him of superficial opportunism. Unlike the masses of visitors who flock to the show, they don’t think much of the radical, fresh visual language Haring uses to address gay culture, AIDS, Apartheid and environmental issues. The alternative art circuit, from which Haring emerged in New York, think that he’s betrayed his roots by associating with art capitalism. The theft of a homo-erotic drawing during the opening, followed by blackmail from artists in the squatters’ scene, put Beeren and Haring in a tight spot. Who could have anticipated that taking art off the streets and bringing it into the museum would precipitate such outrage?

Off the street

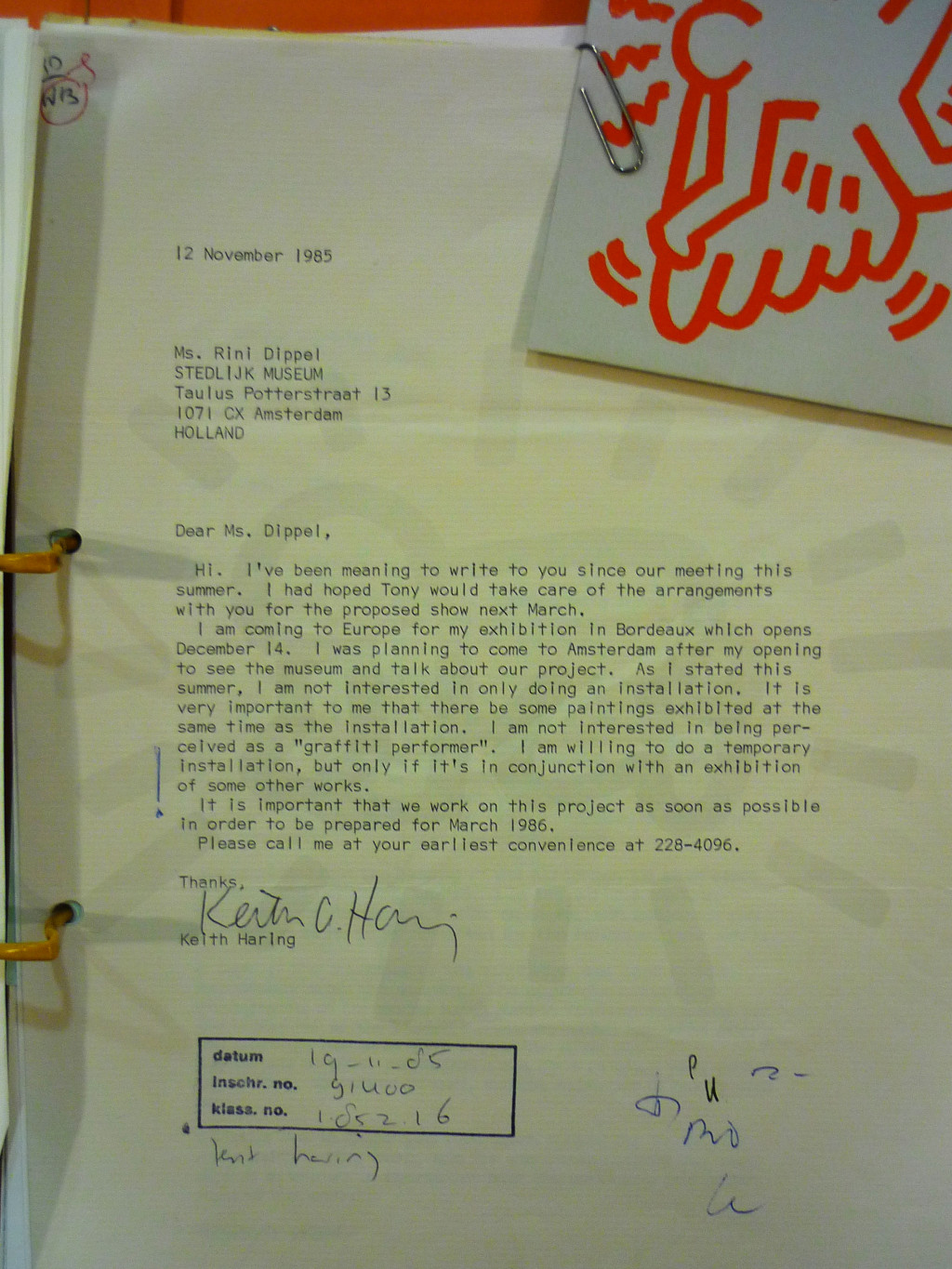

In the summer of 1985, Rini Dippel, chief curator of the Stedelijk Museum, visits Keith Haring in his studio in New York. On 25 November, Keith writes to her, to clarify what they agreed upon. He proposes travelling to Amsterdam after his show in Bordeaux opens on 14 December, to discuss an exhibition at the Stedelijk. 1 Even though he is now represented by the gallery owner Tony Shafrazi, Haring handles the arrangements himself. It seems as though both are pursuing a strategy aimed at clearly positioning the ‘media product Keith Haring’.

Haring unequivocally sets out his conditions in advance:

As I stated this summer, I’m not interested in only doing an installation. It’s very important to me that there be some paintings exhibited at the same time as the installation. I don’t want to be presented simply as a ‘graffiti performer’.

That may be so but, at the same time, Haring is aware that making his work live is his unique selling point. It’s a way to engage with a younger audience, not simply traditional museum visitors.

On 30 May 1984, when presented with an Italian music award in the Rolling Stone nightclub in Milan, using brush and paint, he creates a wall painting, live, in the TV show ‘Mister Fantasy’.2 Although a little-known show, Carlo Massarini’s art programme brings international pop culture to audiences mainly by airing video clips on RAI state TV.

Keith also calmly explains to the excitable Massarini that he doesn’t make graffiti. “What I drew in the New York subway: that’s graffiti because it’s illegal.” Massarini: “You took your work off the streets and into museum and galleries…” Haring: “Over the last three years, I’ve worked all over the world. And yes, if you do something in New York that people like, the whole world knows. We’re living in the space age.” Massarini: “I know I’m not meant to ask you what this work’s about, but what is it about?” Haring: “I think about the problem of how you can ideologically approach technology and where it’s leading, and how you can still be yourself. Capito?”

When Haring exhibits in Amsterdam, TV presenter Bart Peeters interviews him for Flemish TV. In the intro text, Peeters says that Haring “has been given the go-ahead to blot all over the walls of the Rijksmuseum”. 3

Alternative and unknown

Keith Haring’s international career gets off to an albeit quiet start in Rotterdam. Galerie Black Cat on the Mauritsweg shows work by Keith Haring as early as 1979.4 The Amsterdam gallery director Barbara Farber places a painting by Haring on sale in her window for 5000 Dutch guilders (€ 2200).5

In 1982, Gosse Oosterhof (Rotterdamse Kunststichting) invites Haring to mount his first European one-man show in Galerie ’t Venster. This city-run art initiative provides a platform for avant-garde international art that hasn’t yet debuted on the museum circuit.

The Hague-based Fluxus artist Bob Lens is a frequent visitor.6 His regular stays in New York nurture his interest in new American art:

In those days, the New York art scene was ‘cooking’. In June 1980, Keith Haring and Jean-Michel Basquiat made their break- through with the Times Square Show,7 an exhibit organised by Collaborative Projects Incorporated (Colab) and Fashion Moda. The artists who took part were free to choose the works they wanted to hang, or what they did.

And in Amsterdam, as established galleries gradually become more and more out of reach too, artist collectives begin to spring up, squatting semi-industrial premises.

In 1979, W139 opens on the Warmoesstraat, followed three years later by the Aorta collective in the old printing press hall of the NRC newspaper building on the Spuistraat. Gallery owners and curators, like Oosterhof, trawl these breeding grounds for talent, although this is not a prelude to a meteoric American career. During this time, things are complicated by the phase-out of the BKR, a state-run scheme offering artists payment in exchange for artwork. The government requires artists to focus more on selling and – first and foremost – to promote themselves more energetically. But this ends up by disqualifying emerging artists, the group for whom the BKR was originally intended, from the scheme. Artists react by establishing their own non-commercial exhibition venues where they show their experimental, often unsaleable, art.

On 26 March, Bob Lens chats with New York gallery director Barbara Gladstone during the opening of Vernon Fisher, a Texan painter, at ’t Venster. Does she happen to know who makes the chalk drawings on the empty black advertising boards in the New York subway?8 Lens even rode an entire subway route specially to see the exciting, new-style chalk drawings.

“That’s Keith Haring,” she says. “He’s showing here next. I have a few proof prints of his lithographs if you’d like to see…” Lens goes through the prints and orders one, which Gladstone sends him later. She calls him with a question. “Could you give Keith a few pointers when he visits Holland? It’s his first trip to Europe and he’s still very young.”

What Gladstone is really asking, is whether Haring can stay with Lens while visiting Holland. Because he’s going to make work for the exhibition ’t Venster too, Haring extends his stay. Bob and Ellen Lens, and their infant daughter Sarah-Mezjdah, live in a part of Museum Panorama Mesdag in The Hague. Haring is welcome, says Lens. The family can put him up in Sarah’s room.

Keith and his host hit it off – when it comes to age, Lens could be Haring’s older brother. Lens tidies up the guest room and cleans a couple of school chalkboards. On the first night, using a piece of white chalk he finds in the room, Keith makes two drawings on the blackboards: a pyramid, a staircase, and flying people. The drawings are never finished – the chalk runs out.9

On 29 April, the day before Haring gets to work in Rotterdam, Lens takes him on a tour of the city. They drive through The Hague, past a mural Lens made in the neighbourhood known as Laakkwartier. “It’s a working-class neighbourhood where they once stripped a beat cop, then sent him packing,” Lens tells Haring. “But if you get to know the people a bit, they respect you. They helped me paint it – local people of all ages. And they’re always happy to see me when I drop by.” Lens’ story resonates with Haring. Keith says: “My subway drawings were also a way for me to communicate with people on the street.” Which is something he seems to miss. “I love working with children. I’d really like to make playgrounds.”

Bob drives to Scheveningen to show Keith the herring warehouses. [Herring is haring in Dutch] Yes, Haring’s forefathers were Dutch. Sometimes he signs a work with a little figure holding a fish over his head.10 Haring laughs at the name of the hotel – Badhotel, bad hotel. 11

Next, they visit the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag – Mondrian– and then Haring insists on going to the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam to see CoBrA, Alechinsky, Lucebert, Dubuffet. He feels a connection with them. With their work, that he knows only from art books. He is also invited to an exhibition of Robin Winters, an artist friend from New York. Winters is showing at ‘The Living Room’, the alternative art venue in the living room of a house on the Wagenaarstraat in Amsterdam East [home of Bart van de Ven and sculptor Peer Veneman]. Lens: “We went there as well. Rob Scholte met us there. They chatted for a while.” After that, Haring works for two solid days in ’t Venster: he pro- duces around twenty-five drawings on paper, and throws none of them away.12 He also paints the gallery’s huge window, on the first floor of the Oude Binnenweg. And is delighted by finding a Donald Duck t-shirt. “In dollars, that would cost just $ 8. I’ve never seen prices like that in New York.”

From where he works, behind the first-floor window, he witnesses the Queen’s Day festivities, and also spots a silver foil Mickey Mouse balloon. Keith wants one just like it. Willem Oorebeek, the gallery assistant, goes off to buy one. Mickey, but now without his ears, appears in a drawing with two cheering figures and the vertical letters USA.

In between, someone from Poetry InternationaI visits. To see if Keith would like to make a drawing with cabaret artiste and comedian Freek de Jonge. OK. Haring draws De Jonge bending, stiff-limbed, surrounded by his slogan “Kunst is een knieval voor de tijd” [Art is kneeling down for Time] and leaping figures with a dice.13

Barbara Gladstone appears again at the opening. This time in the company of her friend Tony Shafrazi, an artist and art dealer who pays Haring to do odd jobs around the gallery. Also present are Emmy Tob and Monique Perlstein who will present Haring in 1983 at their venue, Galerie 121 in Antwerp.14 However, they don’t buy anything. The dollar is too strong. Which prices a Haring drawing at $ 500: 1250 Dutch guilders, which today would be € 570. Too pricey for potential buyers. For Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, curator Geert van Beijeren buys the drawing ‘Fuck You’ (directed at art critics).15 No other sales are forthcoming. Only Oorebeek buys, for $ 100, € 114, an absolute bargain, Haring’s only drawing with words written in Dutch: “gele engel” (yellow angel). It is an in memoriam. The exhibition attracts little media coverage. Only Paul Groot writes a thoughtful review, plus interview, which is printed by Dutch daily paper NRC Handelsblad.16

Haring seems more serious than the exuberance of his work may suggest. He explains to Groot how, in his subway drawings, he wants to avoid both the ‘abstract-suggestive style’ in the manner of Alechinsky, and personal, political or sexual unambiguity. So “not too many exploding nuclear reactors, TVs or men with cross- es and knives.” Two months after Rotterdam, Haring will participate in the Documenta, the international contemporary art exhibition in Kassel that is hugely influential on museums’ exhibition programmes. He exhibits work that he co-created with L.A. II (Little Angel alias Angelo Ortiz, then aged 15).17 Tony Shafrazi has offered Keith a show that autumn, inviting him to transform the gallery into a nightclub. Basquiat, a fellow participant in the Times Square Show, was claimed by a gallerist before Haring. In contrast to Basquiat and his domineering gal- lery owner, Shafrazi gives Haring all the space and freedom he needs. Haring will show painted tarps, sculptures and drawings, and also has the green light to decorate the walls.

Previously, Keith has confessed to Bob Lens that he’s afraid of losing his freedom by becoming a professional artist:

But if I’m to paint all the time, I have to give up my side jobs – cook or flow- er delivery guy. I want to live from my work but the art business pushes up the prices. You can’t avoid that as an artist.18

To Paul Groot (NRC Handelsblad) Keith says: “The irony […] is that the decorations were made for the street, but are being accepted as bourgeois in no time. It’s great to be in that system, of course it is, but I know enough about it to be sceptical.”19 Lens: “He undoubtedly made street art that was more elitarist than most graffiti.20 Keith was far more knowledgeable. I thought he worked more intelligently than the other graffiti artists.” Haring’s fame precedes him – in New York, not so much in Rotterdam.

The Dutch collectors Martijn and Jeannette Sanders are also familiar with his work. They make a trip to New York to see Haring’s exhibition at Shafrazi’s gallery. There – and not in Rotterdam at the previous show – they will buy his work. There, they witness his overnight success. Keith walks ahead of them, on his way to the gallery. Drawing figures with his finger in the dust gathered on parking cars. For Jeannette, this is evidence of just how obsessed he is.21

After his exhibition in Bordeaux, in December 1985, Keith Haring travels to Amsterdam for an initial meeting with Wim Beeren and Dorine Mignot of the Stedelijk Museum. They talk about the Haring exhibition the Stedelijk intends to organise in March 1986. On the evening of his arrival, Haring goes for a stroll in the Vondelpark, close to the Atlas Hotel where he’s staying.22 There, he meets Shoe, Niels Meulman (1967) and Yan, Jan Rothuizen (1968).23 They guys are going to see a piece they made not long before in the Van Eeghenstraat next to the Vondelpark. On the wall of a clinic and institution for psychiatric patients, they’d sprayed the upbeat words BETTER TIMES; in purple. The boys approach to find Haring gazing at the piece, deep in concentration.

Joking, Jan says: “It’s not free, you know. Penny for a peek.’ Haring: “‘scuse me. I don’t speak Dutch.” Jan recognises him from magazines: “But you are Keith Haring!” Haring grins: “I know.” The three talk. Hang out a bit, share a joint. They get the feeling their new friend’s feeling a little lost. Haring tells them he’ll be showing work in an exhibition in Amsterdam in a couple of months.

They assume he’ll be showing at Yaki Kornblit, the gallery for American graffiti art, on the Willemsparkweg not far away. Niels and Jan often go to exhibitions there with ‘Joker’ (Thomas Termaat, 1968) ‘Delta’ (Boris Tellegen, 1969) and ‘Jaz’ (Jasper Krabbé, 1970). The group – with the exception of Jan – operates together as the United Street Artists and adores the American graffiti artists that Yaki presents. Jan asks Keith if he knows Dondie White and Futura? Zephyr? He loves their work. Keith knows them all but – no – he’s not going to show his work at Kornblit; he’s going to show at the Stedelijk.

The guys plan to meet up later and do something together. Why not in the Vondelpark? Niels and Jan know a couple of good spots there. A few days later, they wander through the park. They tag the rear panel of a small building to the left of the park en- trance. Keith nimbly draws a row of dancing figures on the arched bridge, in marker pen. The guys take Keith home with them. Jan’s mother has no idea who he is. She asks Keith what brings him to Amsterdam. A show,” he says. “So, you’re an actor?” Keith shakes his head, smiles and explains.

Niels’ mother, however, knows precisely who Keith is. When she goes up to the room where her son and Keith are drawing and smoking pot to take them a cup of tea, she almost faints. Keith later gives Niels a Haring Swatch to pass on to his mum – to make her shock-proof. Jan: “Our parents were progressive. They thought it was amazing and exciting that we knew someone like Keith, even if he was ten years older than us.” Niels: “Keith drew something in my black book. Which ended up stolen, but I managed to get it back a couple of years later – but without his drawing for me. That drawing turned up at a Christie’s auction in 1994 and was bought by a French collector.”

When Keith next visits Amsterdam, he’s too busy to hang out and relax again with the boys. A journalist contacts them, and invites them to come and watch Keith painting his velum. And, of course, they attend the opening of the show. Later, Jan also cycles to the Markthallen where Keith is working on a large wall painting.

Street noise: sought and found

In 1982, Geert van Beijeren, curator at Museum Boijmans-van Beuningen, attempts to convince Wim Beeren, his director, of the merits of something new like American graffiti.24 At first, he has little affinity with it, but eventually comes around: “... some graffiti artists felt compelled to work with the same concentration [as they worked on the street]. But then creating something they like to call a painting.”25 After Haring’s first European solo exhibition at Galerie ’t Venster in Rotterdam (1982) Beeren looks at the graffiti in the New York subway with a “museological director’s eye.”

For Boijmans, Van Beijeren purchases Haring’s ‘Fuck You’ (aimed at art critics), a large work on paper. In 1983, Beeren presents a graffiti exhibition in Boijmans; with acquisitions: ‘Untitled’ by Haring and traditional New York graffiti by Zephyr, NOC, Seen, Blade, Rammelzee and even their French counter- part, Robert Combas. In 1985, when appointed Director of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, Beeren is bothered by the lack of graffiti artists. He contacts Jean Louis Froment (Musée d’Art Contemporaine, Bordeaux) and, taking practical considerations on board, sug- gests that they jointly arrange for Haring to visit Europe for a shared exhibition.

Few other Dutch museum directors share Beeren’s interest in graffiti. Rudi Fuchs, director of the Gemeentemuseum Den Haag, who later succeeds Beeren as director of the Stedelijk, seems conflicted. At Documenta 7 (1982), which Fuchs curates, Haring is presented alongside the older, stylistically similar East German artist, A.R. Penck. The influential Documenta exhibition barely makes an impression on Keith, who makes only a brief mention of it in his journal. Fuchs considers graffiti a kind of urban folklore. “Everyone raved about Beeren’s graffiti exhibition, but that work will be left to gather dust in Boijmans’ basement for the rest of its life.”26 Wim Crouwel, Beeren’s successor there, is decidedly anti-graffiti. “Not because I do or don’t like the characters, but because they’re identical the world over. You don’t need to go to a museum to see them.”

Frans Haks proves more obliging. As director of the Groninger Museum he purchases only Haring merchandise:

Saying graffiti is all the same is like saying all Chinese people look alike. If you don’t steep yourself in it, you won’t see the distinctions. [...] Some proponents go on to develop their ideas, others get stuck. Nothing unusual about that. If a movement has more or less run its course, it doesn’t mean it was of little value. Jugendstil started out as a passing fad but has now become an institution.

Beeren’s “articles of faith” create resistance. Hardly surprising. As curator at the Stedelijk, Beeren was heavily criticised for embracing Pop Art and De Nieuwe Realisten. As new director of the Stedelijk, he confuses friend and foe with ambivalence and paradoxes.27 He is in step with the zeitgeist and wants the museum to present important topical concerns, yet with a solid respect for art history. Drawing hordes of visitors with what could be a blockbuster Haring show, is not his intention. Beeren reaches out to the art world of Amsterdam. His first exhibition as director, ‘Wat Amsterdam betreft’ (1985-86) reveals his approach, and wins him the confidence of the critical and broad-based Amsterdam art scene. What a difference with his predecessor Edy de Wilde. He had viewed the museum as a filter rather than anything else. Under his directorship the socio-cultural activism of the sixties – ‘provos’, hippies, anti-Vietnam marches – barely found its way into the museum.

In 1969, De Wilde addresses protesting artists from the museum steps, megaphone at his mouth. Art is elitist and the city’s art museum has only one man at the helm: the director. Beeren, however, plans to win back the streets, bringing street noise back into the museum.

During Haring’s opening – Beeren’s first international exhibition at the Stedelijk, the marble staircase beneath the velum is swarming with people. Haring, artist of the street, is where he wants to be: in the museum. In his diary, he writes:

The opening in Amsterdam is even more exciting than the one in Bordeaux. The show has phenomenal attendance. For me, it was an overwhelming experience, showing at the Stedelijk Museum. I felt I had really accomplished something.28

An earlier velum

As curator of painting and sculpture (1965–1971) and later director, Wim Beeren is well-versed in the history of the Stedelijk Museum. And knows of the existence of an earlier, decorated velum: a gigantic canvas that filters sunlight.29

In his first impulse to bring Haring to the Stedelijk, he comes up with a dynamic project that fits the artist’s process. He wants Haring to make an installation for the hall and the staircase, following in the footsteps of Ger van Elk, Luciano Fabro, Gilbert & George, Loes van der Horst, Daniel Buren, Giuseppe Penone and Dan Flavin. Would Haring like to make a velum in the tradition of the Stedelijk? The artist agrees. He also makes ‘Amsterdam Notes’, a wall-filling ink and acrylic paint drawing for the angular, inverted U-shaped print gallery below the stairs. Later, along with the velum that would hang for three years, these will be shown as a frieze among the presentation of new acquisitions in the Hall of Honour.

It is Willem Sandberg, then curator, and director between 1945 and 1963, who commissions the artist and Bauhaus instructor Johannes Itten in 1938 to design a velum, also “to put a bit of money in his pocket.” From 2 to 6 May 1938, Sandberg orders the museum’s brick walls to be painted white. The yellow glass of the skylight above the marble staircase is also replaced by matt glass. Paired with the new white walls, the hall is now blindingly bright. A velum of 18 × 9.5 metres, stretched beneath the skylight, offers a solution. (Haring’s velum measures 20 × 12 metres) The velum is fabricated from marquisette, a calico and linen blend. The fourteen red stick figures are appliqued and stitched onto a pale yellow and grey background. Stylistically, they could be considered the grandparents of Haring’s hip-hopping figures. Both seem to be caught up in an archaic ritual dance reminiscent of ‘Sacre du Printemps’.

While the Second World War raged, the museum was evacuated but the Itten’s velum was left just where it was. The big roof window smashed, scattering fragments of glass that fell, shredding the velum to ribbons. After the war, what remained of Itten’s velum was framed. A sketch on rice paper shows how Itten’s velum would have looked. In 1991, the museum exhibits the surviving sections of the work, alongside several sketches – and makes no reference to Haring’s velum which, by that point, was five years old. Today, an advanced lighting system means the velum is no long necessary.

Non-stop exhibition: keith paints a velum

A huge section of plastic sheeting covers the ground of the first floor of the New Wing. On top of it – taped down at the edges – is a canvas, a velum, used to filter bright daylight. Surface area: 20 × 12 metres, as large as the Hall of Honour.

The Stedelijk Museum did not buy a new velum. Haring is gets to paint on a used one. Here and there the fabric is laddered, but the flaws have been repaired. Threads hang from some of the eyelets in the seam. Only a wuss would make a problem of it. Keith doesn’t. The fabric is Trevira CS Col 30 Permalese, fire retardant polyester furnishing fabric.30 Weft (horizontal) and warp (vertical) wrap around each other, and the loops are enclosed in a synthetic coating. From a technical standpoint, polyester and aerosol paint are a good combination. Possible complications could involve the spray melting the yarn, or the textile repelling the paint. But that doesn’t happen. In spray paints, the particles are dissolved in alcohol and attach themselves to the fabric immediately. Keith often works on unconventional surfaces – plastic tarpaulin for example – and isn’t bothered by unfamiliar material.

The fabric’s fantastic, a bit like cheesecloth and with an open weave. It’s impossible to paint with a brush, so I switched to spray paint.

No need to make a preliminary sketch: Keith immediately gets busy, spray-painting the velum.

Niels Meulman helps out with the spray paint. He chooses Sparvar, the brand always used by the United Street Artists.31 The retail price for a can is twenty Dutch guilders (€ 9). Keith will need around 500. He buys them at Hein Kuhlman, a paint store at 138 Jan Evertsenstraat. Graffiti artists buy such large quantities that Kuhlman gives them a 50% discount. Spray-painting on a fine, open fabric means that around 30 to 40 percent of the paint penetrates the weave. Which filters the colours. The paint seeps through to the plastic sheet underneath, making a kind of print; but the plastic sheeting is thrown away afterwards.32 There’s proportionately more paint on the underside of the velum (the side everyone sees) than on the “sprayed” side on the top.

Keith wears a black sweater over a T shirt printed with one of his own designs. Shoeless and in white tennis socks, and with extraordinary energy and great rapidity, he literally hip-hops his way across the expanse of velum. The sweetish scent of spray paint wafts towards the restaurant, that adjoins the New Wing. The Kenny Scarf-decorated boombox spills out hip-hop beats. A stack of cassettes is at the ready: salsa, merengue, soca, breakdance, Grace Jones (Keith body-painted her in 1985 at the Paradise Garage performance in New York) The B52’s, Zoolook by Jean-Michel Jarre, Bronski Beat, Talking Heads, Stevie Wonder, old torch songs by Eartha Kitt. Under Haring’s hands, the hip-hop dynamic transforms into a rhythmical choreography of figures dancing and bouncing across the velum.33

Crouching over the velum, he spray-paints the first figure in a corner of the canvas. It’s a kind of genie escaping from the bottle: an elongated figure with upraised arms and – instead of legs – a tornado. Tornado figures will spiral from every corner, and three times, a crawling baby appears next to them.

When the dancing figure is finished, Keith kneels and brings his face six inches above the velum. That’s how he can tell if the direction points diagonally towards the middle. Yes! Haring works systematically, with such an accurate hand that his work needs no correction. First the edge, then he works towards the centre, filling the rest with black figures. One by one, they leap from the can, straight from his subconscious. They could be Egyptian hieroglyphics or Mayan reliefs reimagined for the 20th century. UFOs, pyramids and Haring’s personal versions of Mickey Mouse and Batman. As the velum begins to fill up, Keith varies the poses and gestures. Coloured cartoon-style movement lines around the figures inject an extra dynamic.

The occasional glitch occurs: the spray nozzle blocks, squirting the paint out in blotches. When that happens, Keith holds the can upright and shakes it vigorously; the mixing pea rattles. As the can begins to empty, the edges of a figure go fuzzy. But that doesn’t bother Keith who says it’s “part of the game”. Art critics, journalists and photographers have been invited to see Keith painting live. Curator Dorine Mignot arranged for them to be present, with Keith’s approval. It’s just like his New York studio, one of Madonna’s favourite places to hang out and chat.34

Here, Keith keeps a close eye on every visitor. And greets photographers and fellow artists more warmly than critics. Chris Reinewald visits in his role as journalist for youth magazine Plug. He invited the United Street Artists – Joker, Shoe – and Yan as Haring’s young counterparts from Amsterdam, not realizing that Keith knows them already. Haring doesn’t make graffiti, Joker is quick to point out. “Real graffiti is full of letters and characters like the ones you see in the work of Quick and Blade in New York: real graffiti artists.”35

Keith greets the boys like old friends. They watch admiringly at Keith’s skilful handling of the can – he works with an easy, relaxed precision. Scaffolding a metre or two tall is there so that Keith can get a better overall view of the composition. But he hardly uses it. Photographers do. The United Street Artists aren’t very impressed: “We like letters. What Keith’s doing here is more like floral wallpaper. But you’ve got to be positive about this kind of exhibition. He’s the only person who works like that. You shouldn’t want to copy him.” Jhim Lamoree comes to watch. The dreaded art reviewer of the Haagse Post turns up, sharp-eyed and critical, and with an equally critical pen. The weekly is undergoing a redesign, and has planned a cover article on ‘computer fever’. It will also feature articles on kamikaze sex in the AIDS era. Would Keith like to make three illustrations, one of which they could use as a cover? He’ll be paid the usual illustration fee of 750 Dutch guilders (€ 340). Deal!65

Then there’s a special offer for readers: a screen-print by Haring – untitled, 1985 – of one of his paintings. An edition of 500, 100 Dutch guilders (roughly € 45) for subscribers, printed by George Mulder, a Dutchman living in New York, who also produced Warhol’s queen screen-prints. Haring gets to work. Armed with a stack of A4 sized sheets, a narrow black marker pen and a bottle of Tippex, he swiftly draws two men mutually masturbating, and two other, more abstract, drawings. And jots down notes about accent colours. Done. The finished cover drawing depicts dancing men carrying a white figure with a computer on their shoulders.

In the museum restaurant, Keith makes short work of a salami baguette washed down with Pepsi.37 The Plug journalist sits next to him and asks Keith what he thinks of the United Street Artists.

Hey, what is this? An interview or something? Hmmm, what surprises me is that they’re white and from nice families. The kids in New York are from the street. And here, young guys are imitating what’s being made in New York. And they do a good job, but it could do with being a bit more inventive.

He gets up and returns to his painting. When the velum is full of figures, he colours them in. Purple, green, red, yellow. Keith, satisfied: “I painted the entire thing in a couple of hours.”38

The velum is installed the following day. Everyone is amazed by how Haring’s bright colours flood the hallway with a pastel-hued Impressionist light.

Tseng Kwong Chi, Haring’s friend and photographer who always documents his work, arrives. Tseng photographs everything. Bursting with energy, Keith leaps onto the marble staircase ban- nister beneath the velum and strikes a pose!

Benny, baby and batman

Photographer Patricia Steur and her husband, tattoo artist Henk Schiffmacher, make reportages for the weekly magazine Nieuwe Revu.39 She also photographs Keith and the velum, and per- suades him to leap into the air in front of a painting. She tells him about Henk’s tattoo parlour. Keith’s impressed. Keith: “Cool! Can I tattoo my friend?” Patricia: “You can, but you should have some experience.”

A couple of days later, Keith turns up. With his friend, Benny Soto, who also works as his assistant. Keith met the skinny Puerto Rican teenager in 1984, when he was volunteering for a Catholic community centre. In spite of being a grade A student with plans to study medicine, Soto becomes addicted to crack (rock or crystals derived from powdered cocaine that are smoked).

Haring employs Benny as his general factotum, which gradually helps him to kick his addiction, and brings him to Amsterdam. It’s Benny’s first trip to Europe. Keith lets Benny get tattooed. An atomic baby and a Batman on each upper arm. Haring:

The babies are electrically charged. When you crawl, you’re halfway between a two-legged adult and a dog. So, the baby is a kind of nature-culture hybrid.

The velum is alive with crawling babies, Batmans, dancing men and octopi. Henk Schiffmacher tattoos the contours and lets Keith colour them in. When the work’s done, Henk saves the used needles and the blood imprinted on the cloth used to gently dab away the blood left by the tattoo wound. At Henk’s request, Keith signs the print.40

Because the artist had enjoyed tattooing so much. Henk tells Keith where he can buy his own tattoo supplies in New York, at Spaulding & Regent. The event inspires Henk to ask artists to create tattoo designs, to be tattooed exclusively by Schiffmacher. Warhol agrees to take part but the project ends up being shelved prematurely.

Ozon layer

The exhibition opens this afternoon, 15 March, at three o’clock. Earlier, at eleven thirty, Keith gives a lecture in the auditorium. An informative talk with slides of his projects and his life story; it all feels a little routine. He’s clearly given the talk before. Keith speaks, seated on the corner of the stage in his favourite position: a casual cross-legged pose. When his talk is over, he scatters badges with Haring designs into the audience.41 With his obligatory lecture out of the way, he agrees to be interviewed by a local Amsterdam TV channel on the terrace of the museum restaurant next to the New Wing.42

Keith clearly has to psyche himself up to talk to his interviewer, the spikey-haired high priestess of punk and performance poet Diana Ozon. He’s not very fond of journalists and art critics, it seems. But Ozon reminds him that she met him with Hugo Kaagman, a graffiti-artist, two years earlier during the Milano Poesia in Galleria Salvatore + Caroline Ala.43 Keith feels far more at ease. OK, ask away. Ozon opens with a tough question. Does he see connections between the Libyan dictator Gaddafi, Reagan’s rhetoric of war and cultural terrorism which, according to critics also includes graffiti?44

Haring is lost for words and looks helpless. Behind him stands a young blonde man with a flamboyant new wave haircut. In one hand a Haring exhibition poster, in the other, a black marker pen. It’s more than obvious that he wants a signature. Quick, now, in a minute, if you please. Ozon dials it down a bit, with the help of her friend Hugo Kaagman. Wouldn’t it be great, he says, if Haring’s show inspires the city council to legalise graffiti, as it’s done with soft drugs? And: after Haring, will the Stedelijk take Amsterdam graffiti seriously? Once again, Haring is quick to make clear that he doesn’t make graffiti. And wonders to himself whether Ozon paid any attention to his lecture. He says that he travels the world, making art for the public space. He never uses spray paint, only chalk or Japanese ink when he draws. The only time he used aerosols was to spray-paint the figures onto the velum.

The new wave boy is still waiting patiently. And, to be on the safe side, pulls the lid off the marker pen with his teeth. And is the first fan to get a poster with Keith’s autograph.

Haring good-naturedly tells Ozon that legalizing graffiti would help a great deal. It would give artists more time to make a piece. They wouldn’t be in fear of police turning up. And not being accused of vandalism would bring a huge sense of satisfaction and validation. That’s why in New York they should stop spraying graffiti all over the subway trains. Cleaning off tags costs the city council a lot of taxpayers’ money. Which could be better spent on murals in poor inner-city communities. Graffiti artists and locals working together to brighten up their neighborhood. Kaagman and other graffiti artists snigger. Isn’t Haring betraying the ideals of American graffiti? Any more questions? Yes, why does he wear a face mask while he’s spray-painting?

“You don’t want to breathe in the propellants. They’re bad for your health. And for the ozone layer. I don’t want to die before my time.”

Mayhem in gallery 223

That must have been an incredible sight for the staff of the Stedelijk – and particularly Wim Beeren. Another long line of people is waiting patiently on the Paulus Potterstraat in front of the museum entrance door. The opening of Keith Haring’s show will attract around three thousand visitors.

There are many young people, as well. They hand their skate- boards in to the Cloakroom attendant.45 Artists too, some from the hardcore squat scene. Some feel much the same way as the art critics – not convinced that Haring has earned his place in the capital’s temple of art. He’s come out of nowhere, and sold out to capitalism by being hyper-productive. Roel Vlemmings, originally from Eindhoven but who graduated from art college in Maastricht, has just moved to Amsterdam. The economic crisis of the late eighties prophesies a bleak future for young artists. Which makes Vlemmings enjoy the opening even more:

It was a fantastic trip, the energy of a disco. A real party for art.46

Hundreds of people squeeze through the galleries and art spaces. Haring exhibits large paintings in the Hall of Honour. Then there’s the velum and a wall drawing that fills the entire print gallery, halfway up the stairs. Gallery 223 is crammed, floor to ceiling, with nothing but drawings. They’re not presented behind glass as in a traditional presentation, but pinned up with thumb tacks: informal and anti-authoritarian. The centrepiece is a series of seven early ink drawings that Keith made in 1980 in the artists’ workshop centre PS 122 in New York.

By Haring’s standards, the series is not as energetic as the work he makes now. It lacks the flair of his recently executed wall drawing. Haring drew that with a pointed Japanese brush, which creates a varied line width. The earlier series is designed along the lines of a religious Stations of the Cross or comic book layout with thick contours, and follows the same kind of narrative. A sequence of scenes depicts a naked black man who hovers, and emits rays of light. Then comes a naked white man – holding a club. He uses it to beat the black man to the ground, but he con- tinues to float.47

The white man pulls the black man to his feet, forces him face- down across a table and penetrates him; the “black” energy becomes swallowed up by the rapist’s club. The last image shows the triumphant white man brandishing a club that sizzles with energy. The black man has been robbed of his ability to fly and to emanate rays of light.

Haring:

The series is about the violent theft of spiritual power [...] How whites appropriate black culture. But it’s a metaphor for many other things too.

Around three o’clock, in an increasingly packed room hung with drawings, a confrontation takes place. In the centre of the room, Haring is talking animatedly with visitors, including the immaculately-coiffed Paul Maenz, the influential gallery owner from Cologne. Haring exhibited with him two years ago, and painted his naked boyfriend, live, at the opening.

Two leather-jacketed young man approach Haring aggressively. They call themselves Josje Picasso and Erik de Schuimer. As representatives of the Stadskunstguerilla (SKG) – also known as the Kultur-Polizei – their goal is to use anarchic tactics to undermine the established art scene.48 Josje is drunk and taunts Keith: “How many did you fuck up the arse to get into the museum?” Keith hates negativism. He ignores their jibes, turns his back on them and moves off. Then Josje goes over to the series of drawings on the wall. And pulls down the rape drawing. Bam! Folds the drawing in four, stuffs it under his coat, and grabs his friend. “Erik, let’s go. I’ve got something special for you.” The two guys leg it. Among the bystanders, Roel Vlemmings also witnesses the incident.49

He’s bemused: “Everyone sees what’s happened and just stands there, doing nothing. Or yells: “Hey, moron, what the hell are you doing!” Vlemmings casts about, looking for someone to help him, but there’s no response. It’s as though everyone’s thinking “So what, we all do things we shouldn’t now and then.” Typical Amsterdam attitude it seems. Vlemmings is shaking in his boots. The guys look tough. Are they punks or hardcore criminals? He can’t let them get away with it, even though he’s scared of getting a knife in the ribs. He gives chase, but loses sight of them in the crowd.

In the men’s toilets, Josje hands the drawing to Erik. “Keep it for a bit. I think they saw me." Erik takes the folded-up drawing and leaves the toilets. He’s spotted by another witness who follows him. In and out of the museum galleries. Erik decides to do a 180. Literally. And starts to pursue his pursuer.50 The witness gets cold feet and backs off. Good. Erik leaves the museum, takes the drawing home, and returns, cool and collected, to the opening. Someone comes up to him right away. “Did you just steal a drawing?” “How the hell would you know?” bluffs Erik, and melts into the crowd in search of Josje. Meanwhile Vlemmings speaks with a museum guard. “Someone’s just torn a drawing off the wall.” The guard listens, but takes no action.51 “Maybe that’s the protocol in these situations, to avoid panicking the crowd.” Vlemmings sees Wim Beeren. Five metres away. Although Vlemmings only knows the director from photos, he goes over and tells him what’s happened.

To his surprise, Beeren doesn’t react – either verbally or physically – to Vlemmings’ bombshell, even though there’s still time to grab the thief by the collar of his highly distinctive leather jacket. Vlemmings goes home, his first confusing introduction to the Amsterdam art scene etched into his brain. Beeren rushes to room 223. A group of people is clustered at the empty space between the six remaining drawings.52 Tony Shafrazi, Haring’s New York gallery owner, is seething with rage: “No security! And where’s the police? This sort of bullshit can only happen in Holland.” “That’s rich coming from you!’ retorts Paul Groot, editor in chief of Museumjournaal. “When you were a teen you spray-painted Picasso’s Guernica.53 So, you’d become famous. And you bought paintings for the Shah of Persia. Keep your big mouth shut!” Beeren, breathless with exertion, jabs at finger in Groot’s direction and roars accusingly: “Your pals did this!”

In the reception in the museum restaurant, Keith is surrounded by people dismayed by what’s happened. They console him. “I’ll kill the guy who stole your work,” yells a photographer at the bar.54 Erik and Josje are facing him, at the other end. Everyone seems to know the identity of the thieves: it was them – the “activist” artists of the SKG from the alternative art scene’s lunatic fringe. In the squatter’s scene, everyone feels entitled to take whatever they fancy. It’s us or them – no middle ground. So why not take a drawing? Vlemmings can’t stop thinking about what happened. A few days after the opening, he phones the museum and says, once again, he witnessed the incident. He gives his name and number, no address.55 The man on the other end of the line misspells his name: Roel Lemmings. Now, Vlemmings waits; surely someone – the museum or the police – will phone him. But that doesn’t happen, either.

Erik and Josje also wait – expecting a call from the police. But that doesn’t happen. They hang the drawing up in the corridor, above a racing bike that’s kept indoors so it won’t be stolen if it’s left out on the street. But for Keith, the theft of his drawing has cast a shadow over the opening. He is upset. “Without that drawing, the whole series is ruined.”56 Haring had been planning to keep the somewhat older series for himself, but shortly before, the museum of Bordeaux had convinced him to sell it to them. For the time being, the Stedelijk hangs up a photocopy of the image, made to the same scale, in the space left by the original, in preparation for Sunday when the exhibition opens to the general public. The museum circulates a photo of the drawing to the press and TV. Keith is amazed that the subject – white man fucks black man – makes no impression whatsoever. “Amsterdam isn’t shocked by pretty much anything.” He continues with his plans: a wall painting outside and a workshop for junior school children in the museum.

Nightlife and no sleep

Haagse Post journalist Jhim Lamoree knows Haring and his scene from New York. Jhim is also invited to the dinner arranged by the Stedelijk for Haring and his entourage – which includes Tony Shafrazi, the Diba’s (a Persian couple) and Jeffrey Deitch, then a consultant to the Citibank art collection – at the Américain.57 Later, Lamoree hears whispers that Keith “parties hard” in the Amsterdam gay scene. Keith leaves before the end of the dinner. Lured by the city’s nightlife?58

Photograph Paul Blanca took Haring to Henk Schiffmacher, the tattoo artist, where Theo van Gogh the filmmaker also hangs out. The guys are planning a night out, which begins with drinks and a few lines of coke.59 At the opening of the exhibition, Niels Meulman is impressed by Keith’s New York friends. “Gay Latino’s with baseball caps: I didn’t know they existed. Keith wore white high-top Nikes. You couldn’t buy those here back then.”60 Keith is gay but doesn’t make a big deal out of it. Schiffmacher calls Keith an “art guy not a gay guy”. Tough and a bit macho, with two sides.

In late 1985, Niels Meulman and Jan Rothuizen also go out with Keith in Amsterdam. He likes hanging out with young straight kids – like Niels and Jan – but nothing happened between them. When the three go out on the town, the age difference – ten years – causes them a bit of bother. The Mazzo, a club on the Rozengracht, frequented by artists and international pop stars – won’t let them in. The doorman says: “too young, wearing sneakers, and no girls.” Niels tries again: he points to his American friend. “Do you know who that is? Keith Haring!” The doorman changes his tune. But then Keith says: “If this is how it is, I’m not going in.” They go to Richter or Korsakoff on the Reguliersbreestraat.

When Keith stays with Bob Lens and his family in The Hague, he readily admits he is interested in young men: exotic types. In New York it’s Puerto Ricans, in Holland he can’t keep his eyes off young Indonesian men.61 Keith wants to explore Amsterdam’s nightlife. Bob finds him a place to stay, with a lady friend who lives on the Keizersgracht. Keith can come home as late as he likes. She gives him a key. Bob is worried: “I didn’t mention AIDS, but I warned him: “I told him to be careful.” And left him to it.’ Keith reassures Bob: “I know what I’m doing, don’t worry about me. I’m immune to everything.” Haring survives on just a few hours of sleep. That’s how he lives.

In 1982, very early in the morning at six thirty, Bob Lens drives him from The Hague to Galerie ’t Venster in Rotterdam where he is going to paint the gallery window. There, his materials are waiting for him: bottles of ink, paint, paper. He gets to work right away, dancing as he paints. Hip-hop blaring in the background. Keith never wants to stop. His New York mindset fuels his obsessive, prolific output. Up, up, up, al- ways too little time. Never stop, make as much as he can. On 20 March 1987 in his journal, Keith writes that he is showing symptoms of AIDS, “gay cancer”:

My friends are dropping like flies. [...] I’m only alive by the grace of divine intervention. I don’t know if I’ll live five months or five years, but my days are numbered.62

Cheap spinoff

Real graffiti or not, the press makes mincemeat of Haring’s exhibition. In his review, critic Jhim Lamoree (Haagse Post) asks a rhetorical question.63 Is Haring an impoverishment or enrichment for contemporary art. As a no-nonsense artist, he grasps the nettle. That’s why he commercialises his work himself. Lamoree asks Dutch artists and contemporaries what they think of Haring. Ernst Voss refers to Haring’s paintings as superficial design. And calls his decorations of Swatch watches and consumables ‘rubbish’. Rob Scholte feels that Haring’s work lacks depth, with which it’s purely decorative. He also sullies himself with a ‘cheap’ kind of social critique when he paints a black man on a leash. Scholte thinks that Haring’s chances of artistic survival are pretty slim. Lamoree’s conclusion: Haring is balancing on a razor’s edge, risking losing his fame through overexposure.

By comparison, almost all the critics are chary with their praise, negative or even denigrating. They feel that Wim Beeren – unlike his pre- decessor Edy de Wilde – isn’t showing the great American art that they admire. De Wilde reserved the Hall of Honour for “his” Americans: Frank Stella, Barnett Newman, Elsworth Kelly and Carl Andre. Beeren breaks with this tradition. Haring now has the honour of showing in this majestic museum space. Later, when Keith hears the gist of Lamoree’s review, he says: “Told you so.” Jan Rothuizen: “He was used to that kind of reaction – that he made too much of the same.”64 Keith couldn’t take criticism lightly. He got agitated. Even when we talked about art together. He couldn’t stand being criticized. Keith was very self-confident. And I think, in the back of his mind, he knew he wouldn’t live very long. He said: “I’m the only one who can do this, and I’ll make it exactly the way I want.”65

Newspapers didn’t think very highly of his work either – they don’t appreciate the content or visual language. “Ex street artist working with well-worn clichés.”66 “Average, too extensive – an overvaluation of American art? Haring’s a passing fad.”67 “Businessman and house painter.”68 Despite his evident political activism – his opposition to Apartheid in South Africa, AIDS prevention – people associate Haring with the burgeoning neo-liberalism of American president Ronald Reagan.

Anna Tilroe, the conscience of Dutch art criticism of the day, denounces American cultural imperialism that is eroding long-standing European values. She polarises:

We either apply other criteria to American art and, like the exotic cultures, exhibit it in a separate museum [the Tropenmuseum] or from now on, we cease to place such high value on our rich cultural heritage. […] Compared to work by the master of decoration Jean Dubuffet, Haring’s […] themes are drab and, even as a phenomenon, such a cheap spinoff that we should fear for the cultural richness of the Stedelijk Museum.69

A few people admire the velum and the way Keith makes a wall drawing at the Stedelijk with a class of junior school kids during a “kunstkijkuur”. With none of the superstar affectations people attributed to him. Dorine Mignot is aware of the controversy the show has generated:

There are a few people here at the museum who aren’t too happy with the exhibition either. But the Dutch art establishment is pretty outraged. Many say that Keith is a graffiti artist, and graffiti belongs in the street – that it shouldn’t be shown indoors. The Stedelijk is certainly no stranger to controversy but our task is to show what’s happening in the art world now, no matter where people think this work belongs.70

Wall painting on the markthal

In Bodega Keyzer, opposite the Stedelijk Museum, Keith sits at a table, alone. All the other tables are fully occupied. Parool columnist Theodor Holman asks Keith if he can join him. The artist agrees. They get talking. Keith wants to know what Holman does. “Dutch writer, not very successful.”71 Keith grins. “It was a long time before I was successful – or wanted to be. All I ever wanted, and what I want now, is to draw, draw, draw.” “You have a great style,” says Holman diligently. “So, they tell me. But style is nothing. It’s the only way I can draw. I’m no Rembrandt.”

He gets up and says goodbye. Holman sees that Keith’s left a napkin behind and unfolds it. No drawing. Just three words: Jan van Galenstraat. Holman slips the napkin into his wallet. And wonders who wrote the words. Keith? Someone else? And why? Art dealer Adriaan Venema enters. Holman mentions the napkin. Venema: “Haring? A hopeless artist. His work will be worthless in another ten or twenty years.” Keith goes to the Jan van Galenstraat where he will paint the side wall of the art storage depot – the Markthal, a former warehouse – shared by the Stedelijk and Amsterdams Historisch Museum. It’s his first glimpse of the building. Dorine Mignot drives him there in her car. Pieter van Oudheusden has come over from Rotterdam, and joins Mignot and Haring in the car.72

In 1982, he met Haring at his exhibition at ’t Venster and is now angling for a follow-up interview. But Keith’s schedule is full. Mignot suggests asking a few questions as they drive to the site. Van Oudheusden agrees. En route, Haring patiently talks – yet again – about his influences: Marvel comics, Andy Warhol, violent media images and his personal religious beliefs, the existence of UFOs –a personal pseudo-religion which today you’d call “something-ism” – and Walt Disney. “I used to draw Mickey Mouse a lot. I don’t any more. For me, he’s a reference to American culture, pop culture mainly. He’s also the only character that’s been with me throughout my life and every- one in the world knows who he is.” Referring to his wall paintings, Van Oudheusden asks Keith if the transient nature of his work gives him a sense of freedom. “It’s also a little frustrating. Making drawings that aren’t permanent, that exist only for the moment and the people passing by. But some drawings are lasting. It’s good to do as many different things as possible.” The car stops. Everyone gets out. Keith: “Which wall is it?” A site manager points to the wall on the west side. “The big one.” Keith: “But I can’t paint that in an afternoon. Scaffolding will have to be built by tomorrow. I’ll need a lot of paint, too. I can make something relatively simply but it’ll take more than a day. In two days I can do a bit more, that’s for sure. But even a single large figure takes a lot of time.”

The storage building is an old chilled warehouse on the Centrale Markt. Stedelijk and Amsterdamse Historisch Museum, both municipal institutions split the management costs equally. This is why the Stedelijk doesn’t need to ask any of the local authorities for permission – not even the Welstandscommissie (buildings aesthetics committee). In other words, it’s legal graffiti. The build- ing is not open to the public.

The head of General Affairs at the Stedelijk Museum schedules the wall painting project for the fourth of March. Ben Haring, nearing retirement, is proud to carry the same surname as Keith, and makes an extra special effort.73 Ben Haring contacts equipment lease company Boogert and hires a yellow scissor lift sometimes used by the museum staff when they hang up banners. Standing on the orange platform, the hydraulic lift operated by a Boogert employee, Keith has all the freedom he needs. A broad bristle brush and tub of white paint are provided.

Keith starts painting at ten thirty in the morning. Freehand, he paints a kind of sea dinosaur with a figure on its back. He starts at the belly and works up from the right to the forelegs and the head. Patricia Steur photographs the painting process. She also gets onto the platform next to Keith to photograph him in action. Because of the wall’s porous brick composition, the paint is absorbed into the surface and he needs to keep thickly reapplying the paint to achieve the thick, unbroken white line. When he’s finished, he signs the piece at the bottom: three Andreas crosses and KH86. By six o’clock, the work is completed.74 Jan Rothuizen has cycled over to take a look. “Keith had got the scale a bit wrong. He had a slight problem making the curve towards the lower body.”75 Mignot admires Keith. He painted the exterior without a steady hand; not a single wrong stroke. “He didn’t get out of the hydraulic lift to check how the piece looked from the ground – not once.”76 In spite of this, the Stedelijk makes no effort to publicize the wall painting.

Later, Beeren calls it Keith’s gift to the city. Every day, thousands of people can see the Keith Haring mural, for miles around.77 But the wall painting disappears after a couple of years. For reasons of climate control, sheets of weatherboarding are installed on the exterior, hiding the painting from view. Not long after, the Amsterdam museums, now no longer municipal facilities, leave the building, which resumes its former function of market hall. In 2011, project development company Ballast Nedam plans to rezone the site, and the mural is a point of discussion. If the site is redeveloped for residential use, the Haring mural would make an amazing attention-grabber. The Markthal building, however, is in a poor condition. Would it be possible to demolish the structure but retain the Haring wall?78 The Keith Haring Foundation, custo- dian of Haring’s estate in New York, gives the plan its support.

In Amsterdam, Aileen Esther Middel says that she knows for a fact that the painting “isn’t in bad condition.” Under the artist name Mick la Rock, she’s been a graffiti artist since the age of thirteen and is a contemporary of the United Street Artists. She’d love to see the Haring again.79 For Niels Meulman the wall painting symbolizes a period in Amsterdam when street art – as graffiti art is now known – was really in the limelight. But preferably with a city curator for out- door art because graffiti is often badly maintained.80 For the time being, the security guard at the Markthallen doesn’t allow any unauthorized personnel to see the hidden Haring. Yes, he knows of its existence. “I studied art history, and a photo of the work used to hang here.”

Try not to paint as many dicks

Keith always loves working with kids and wanted to be a dad, like his friends Kenny Scharf and Francesco Clemente. “Kids learn from me, and I learn from them,” says Keith. That’s why he can’t wait to work with a group of twelve-year-old kids from junior school ‘De Kraal’, in de Laing’s Nekstraat in Amsterdam East, a large multicultural neighborhood.

This time, the kids school trip to the Stedelijk isn’t just about looking at art. Afterwards they do a workshop with Keith Haring. And make a drawing together, on lengths of paper that stretch over three walls. First, the class sees his exhibition. The cheekiest boys laugh at the Mickey Mouse figures cheerfully pleasuring themselves.81 “You don’t have to be an artist to draw that, do you?”, asks someone. “Good question,” says the teacher. “We’ll talk about it later in the group with the artist.” He turns to the others. “No running in the museum, alright. And you – don’t lean against the paintings. That’s never allowed, understand. You look at art from a distance. In a museum, there’s only one of everything.”

The kids sit on the floor, facing a painting by Haring.“Look at it for twenty seconds and tell me what you see.” Some kids put all their energy into counting to twenty. Others say that they see lines that turn into figures. Two little men carrying a pyramid up a ladder. Two figures bouncing underneath. Obvious, isn’t it? But the pig suckling eight children at once is a bit more problematic. No one has anything to say about that. Keith comes over. “This is the artist. What would you like to ask him?” “Did you always want to be an artist?”

Haring talks about art college, and that he left it because it was more fun to draw on empty, black advertisement boards in the New York subway. “With white blackboard chalk. That really stood out from the colourful adverts. When people started stealing my drawings, I stopped. That was four years ago. Now, I mainly work in museums. And on the street with adults and children, all over the world.” “Tell the class what we’re going to do, Keith,” says the museum instructor, immediately translating his responses into Dutch for the kids. Keith: “You know the game of musical chairs? We’re going to do something like that. All of you, grab a felt pen. And start drawing something, anywhere on the paper. But you aren’t allowed to finish it. When the lady claps her hand you stop, and start working on someone else’s drawing. Don’t scribble over it. Graffiti artists respect each other’s work. You go on working, in your own style. OK? Right – let’s get started!”

Boys seem to enjoy drawing dicks. Well, if you can draw what you like… They chuckle. Girls try flowers. After five minutes, the museum instructor calls ‘Change!’ Keith draws too. He’s not very tall, and easily blends into the group of twelve-year-olds. Moves about, hunkered down over the paper, nimbly drawing one of his ‘characters’. His drawings look more like annotations – skilful, practiced. And he draws with such concentration it’s clear that he doesn’t con- sider what he’s doing as child’s play. He draws joyously, chatting away in simple English with the kids. “Look: that little man’s holding a radio. Why don’t we draw a cat on his head?” Keith seems completely relaxed – for the first time since arriving in Amsterdam. The multi-coloured wall drawing is finished in an hour. The dicks – Keith calls them “penises” – speedily morph into little houses, trees or cartoon characters. Keith is happy: “Great work everyone, but next time try not to draw as many penises.” To journalist Pieter van Oudheusden, who has also come to watch, he says. “You see them lose their interest in penises after a while, and switch to fairy-tale characters. Getting something like that out of their system was probably the best bit of the workshop.”

Tseng Kwong Chi, Haring’s “court photographer” takes the closing photo: “Everyone leap into in the air and cheer.” Everyone jumps enthusiastically. Keith too. For Dorine Mignot, the workshop is the most successful part of the exhibition.82 “Keith’s a big hero to hundreds of children. He has an extraordinary way of communicating with children. I’ve never seen anything like it.” Which gives her the idea of doing another Haring project aimed at kids. In New York, Dorine Mignot saw a coloring book designed by Haring that was circulated to schools for free. Yoko Ono, the widow of John Lennon, financed the book anonymously.83

The Stedelijk wants to be sole publisher of the colouring book in the Netherlands, and approaches publisher Jaco Groot of De Harmonie. On 19 March, Groot and Haring – “an incredibly friendly guy” – draw up a condensed contract. The contract is for one print run of 3000 copies. A little under half is sold through the museum and city’s art bookshops. Half of the colouring books are gifted to Amsterdam schoolchildren. Keith wants to be “paid” his 10% royalty in the form of books. De Harmonie agrees to the payment ‘in kind’. At the museum, during the opening, the colouring book sells like hot cakes. Gallery owner Riekje Swart buys several copies. And has them all signed by Keith.

On 7 April, Jaco Groot phones Haring for permission to print an- other 3000 copies Keith agrees. The second edition is distributed in the same fashion and today has acquired antiquarian value. When Alex Daniëls alights from the tram, he finds himself face to face with Keith Haring. And recognises him instantly because his father, Lex, owns a gallery. His mother, Ria, runs a boutique and has a Haring-print jacket for sale. The outgoing Alex tells this to Keith. Who immediately wants the jacket. Would Ria let him have it in exchange for a drawing? Deal!84

Kaj Hofman 12, from Hoofddorp, near Amsterdam, loves the Haring exhibition. After seeing it, Kaj makes him a drawing and sends it to Keith in New York. Haring answers – by sending a beautifully decorated envelope. With a Keith Haring T-shirt inside.85 On holiday in August 1987 in New York, Kaj wears the Haring shirt. One day he, his brother and parents, are waiting to take the subway to the Guggenheim Museum. Keith’s behind them. Kaj recognises him but doesn’t dare talk to him. His father’s not so shy. Kaj proudly reveals his T-shirt and talks about their correspondence. “Yes, I remember your drawing,” says Keith. “I don’t send that kind of package to just anyone. Why don’t you all come over to my studio this afternoon… if you have time.” They aren’t the only guests. Keith shows his Dutch visitors cardboard images that are going to be produced in steel. Keith overloads Kaj and his brother with T-shirts, caps and badges and a radio he designed. Then he has to go – to paint a friend’s motorbike. “Will you send me some drawings more often, Kaj?” And Keith is gone. On his bicycle.

Headless haring

After giving a lecture to students at the art school in Utrecht (now known as HKU University of the Arts), Keith turns his words into action. He spray-paints two mirrored figures – one large, the other small – on the lift door in the college building’s hall. Both figures are waving their arms. This is something he often does – make a free piece of graffiti somewhere else, after a paid engagement. But Haring’s painting doesn’t please everyone. The janitor sees what’s happening and takes immediate action. He sprints into the hall to “stop the bloke spraying paint and ruining the lift.”86

Tirso Francés, who heard the lecture, and a group of other students, manage to restrain the over-zealous janitor. Saying: “That’s a very, very famous artist and you’ve got to leave him to it.” The janitor backs off. Although later, another cleaner spots the figures on the lift later on, and attempts to clean off the drawing. He mis- takes it for student graffiti. The cleaner manages to scrape off the head, then gives up. And, for seventeen years, the Haring graffiti is headless and begins to degrade. Opinions are divided. Many tutors feel that, in the true spirit of graffiti, it’s an impermanent artwork and should be left to deteriorate. In 2005, the college board asks conservators of the Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam to restore the decapitated Haring. They do so, painting in the head, not using spray paint. And clean the entire drawing. New generations of students see the Haring lift door every day.

What would Haring have wanted? According to Sanchita Balachandran, conservator and expert in the ethics of conservation, he shared the views of the Mexican muralist David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896–1974). As a political artist, Siqueiros said that the most important aim of his art was to connect with people.

If a work is only [visible] for a day, I want as many people as possible to see it. That’s why I go to so much trouble.87

Returned. but on condition

As directors, Beeren, Mignot and Dippel face a dilemma. They don’t want to involve the police in the theft – a “terrible affair” – just yet.88 In its jokey exhibition review, Het Parool newspaper has given ample coverage to the sensational art theft, live in the gallery.89 A cloud darkens the exuberant Haring exhibition. How could the drawing have been stolen? Normally, security guards patrol the galleries; why not during the busy opening? The directors suspect that the thieves are “pals from the Mazzo” who “must have sniffed something.” Even worse, the drawing – with an insurance value of $7000, around €6000 – belongs to the museum for contemporary art in Bordeaux, an important lender and European partner of the exhibition. In the press, Haring talks about how much the theft saddens him.

Henk Schiffmacher, tattoo artist and journalist at the Nieuwe Revu, and photographer Patricia Steur, become friends with Haring at the exhibition. As luck would have it, they’re also working on a reportage about the SKG. Which means that Henk knows Josje and Erik. Henk promises Keith that he’ll have a word with them.90 After visiting Henk’s tattoo shop, below the Hells Angels HG, Keith gets the idea that the master tattooer is planning to ask the bikers to pay a visit to the two thieves. Haring: “They’re openly saying they’ll give whoever stole the drawing time to return the it themselves. And if they don’t, they’ll exert physical pressure on the group to get it back.” But Henk doesn’t belong to the Angels. “Man, I can’t even ride a motorbike.” Schiffmacher knows that the SKG has the drawing, and swings by. “No physical violence, more a ‘Come on idiots, don’t behave like that. Give the drawing back for God’s sake.’”

In the illegal squatters’ bar ‘De Muur’ in the Spuistraat Erik proudly shows off the stolen Haring drawing. But the “anarchic theft” doesn’t go down well.91 Melle Daamen is on bar duty. In the paper, he read that Haring was particularly attached to this early drawing. “Everyone in the bar said: ‘Come on, this is stupid. It’s not funny.’ We got together, whispered a bit and phoned the Stedelijk and, after a bit of negotiating, agreed that Erik would take the drawing back.” Josje and Erik are prepared to go along with the plan, but on certain conditions.92 In exchange for the work, they want Haring to donate a drawing to Amnesty International so they can sell it at auction. It could generate at least 10,000 Dutch guilders (€4500).

Rini Dippel is relatively relieved. The museum is keen to get the drawing back in good condition. Whether they do so according to the rules, with the aid of the police, or by dealing directly with the SKG. To the Stedelijk, it doesn’t much matter either way.93 Dorine Mignot who, as curator, is the contact person at the Stedelijk, records what she agreed with Josje in a phone call made on Monday 17 March: “Mr. J. A [...] B […] will return the work. If he hasn’t done so by tomorrow, 18 March, the police will be called in.94 Wim Beeren writes to Nadine Meyran, assistant to the director of the museum of contemporary art in Bordeaux. He begins by writing “last Saturday, the opening drew a huge crowd, and can be considered an amazing success.” And then confesses: “Regretfully, we have to inform you that a work by Keith Haring has been stolen.”95 He reports the theft so that the museum can alert its insurance company, and ends on a more positive note: “We have been able to learn the name and address of the thief. If the work is not returned to us tomorrow, we intend to go to the police.” But Erik and Josje fail to turn up. That same day, on behalf of the Stedelijk Museum, Bernard de Graaf files a report of the crime at the police station at Van Leyenberghlaan in Amsterdam-Buitenveldert. A salient detail in the official statement: “My director Beeren originally attempted to settle the matter first with the man [thief], but he hasn’t responded.”96

Haring is disgusted by the blackmail tactics of the “so-called underground” of the Amsterdam art scene: “They’re trying to make it seem as if the theft is an artistic statement so the whole thing has a semblance of credibility. [...] But it’s absolutely ridiculous.97” “I made a small drawing – out of a sort of fighting spirit – to trade with them. Not that I wanted to give it to them: I just wanted the other drawing back.” On the back of the drawing he made for the exchange – a barely recognisable dolphin – Haring writes that the proceeds will go to Amnesty. A week later, on Monday 24 March, the exchange takes place. Josje and Erik, cigarettes clamped between their lips, are wear- ing suits. They come to return the Haring. The Nieuwe Revu is there.98 Patricia Steur takes pictures. When the photos are published, white bars are printed over Josje and Erik’s eyes to conceal their identities.

Keith returns to New York. The director doesn’t appear. Others present include: Ben Haring, head of technical services, Huug Brabänder, commissary, Joost van de Pol, communication, and Rini Dippel. Stone-faced Kitty Janssen, who works for the communication department, guardedly hands over Haring’s exchange drawing to Erik, and receives the stolen penetration drawing in return. Josje grumbles: “I don’t like the drawing much anyway. Give me Karel Appel and Van Gogh any day – not this modern rubbish.”99

The museum does not dignify his comment with an answer. Josje and Erik finally accept the exchange. The Stedelijk shares the good news with the press. “Keith Haring returned.

Unknown thieves.” The SKG want to share its side of the story and calls De Telegraaf newspaper. Around midnight, the paper sends journalists and a cameraman to meet the SKG. They hold up the traded Haring drawing upside down. The radio wants to talk with them, too. Why did Josje steal the Haring? “Sometimes I’m at an exhibition and my adrenaline spikes – and I didn’t have any vitamin C on me. I saw that thing by Haring, hanging from four drawing pins, there for the taking. Yes, I’m a collector.”

The SKG had once tested out “how bad” the security at the Stedelijk is. In the past, Josje stole Van Gogh’s “Man in the Felt Hat”, but gave it back later. Erik: “We’re not interested in the value of the Haring. Money’s not what motivates me. We’re trying to draw attention to Amsterdam artists who never get a chance. We use extreme tactics to create our own platforms.” The SKG sees itself as an artist-led and milder variation of what the Rote Armee Fraktion does. “We know people through graffiti and the street. We see ourselves as terrorists because we want something others don’t. Why does the new director bring a tacky exhibition like this, that’s already toured every world city, to Amsterdam? Down with American domination! Always chasing after America where the “real innovators” come from. “Haring seems to have become such a big shot now, and I want to have some of his work, even if I think it’s dreadful. But I like the fact that he’s so prolific. I can imagine he was sad that we stole his drawing. It’s hurtful. Personally, I don’t hold with stealing. Stealing someone’s paintings at an exhibition is a pretty dirty thing to do. But what bothers me is that museum’s make it so easy.”

On Wednesday, a few days later, Amnesty International responds with a letter. They refuse the “drawing that was acquired dishonestly” and won’t be able to accept the proceeds should it be sold.100 The police reprimand the museum for not informing them of the theft when it first occurred, and of undertaking negotiations with “unknown parties”. On 3 April, Commissioner Dorst writes: “The incident could have provided key information that would play a major role in further investigations into the members of Stadskunstguerilla, and with absolutely no risk of jeopardising your interests.”101 Despite the delay, they police promise the case will gain the priority it deserves. For the moment, Erik is permitted to keep the Haring exchange drawing. But to auction it at Sotheby’s, he needs to pay a fee of sixty Dutch guilders (€ 28) for it to be printed in the catalogue. He doesn’t want to. “It’s terrible. I just don’t know what to do with it.”102

Because the drawing was folded, the ink has been damaged. The museum has restorer André van Oort draw up a report and sends it, accompanied by photos, to the owner (the museum in Bordeaux), and to Keith, as maker. They agree to allow the paper conservator to restore the drawing. It will take at least a week.103 In her letter to Haring, Rini Dippel explains that the SKG consider the theft as the “art redistribution”. “According to them, the SKG do this kind of thing more often.” She also tells him that Amnesty is refusing the drawing because the offer was made not by Haring but by the SKG, who – without Haring’s knowledge – approached the media.

On 15 April, Haring writes back from New York, expressing shock at the state of the stolen drawing. “I don’t have that paper or ink any more. It was cheap material: basic Japanese sumi ink and certainly not acid free paper. If the restorer thinks the other draw- ings need work, he can go ahead, that’s fine.”104 “It’s funny that the kidnappers are photographed holding my new drawing upside down! I’m happy that the drawing’s back, too. But quite disappointed that when the exchange was made, and in the press, the kidnappers have the last word. The exchange doesn’t feel like an honest deal. If there’s any way to press charges, I’d definitely do so.”

A friend to all, but nobody's

Controversial, annihilated by critics, despised by “underground artists”. But so many visitors can’t be wrong. The Haring show attracts such an enormous crowd that the Stedelijk prolonges it for another eight days.105 The museum also buys work: the monumental wall drawing “Amsterdam Notes”, an untitled drawing and two acrylic paintings, one of which is anti-Apartheid.

On 16 September, Tony Shafrazi wires the Stedelijk $ 14.000, Dutch guilders 32.000 (€ 14.520) to pay towards the exhibition expenses.106 In his New Year card in 1987, Keith Haring also thanks Wim and Dorine of the Stedelijk Museum:

Although it’s been a while since my show, I’m still enjoying the after effects. All over the world, I run into people who saw the exhibition.107 There’s no doubt that it was my most successful exhibition up to now. I realised that we never talked about what was going to happen to the ceiling piece [the velum]. Tony and I would like to donate it to the museum. I am very grateful to you all for the sincerity and courage you showed by realizing the Keith Haring exhibition at the Stedelijk. And by buying work, the museum also confirmed your dedication and farsightedness. I hope that the museum will accept this gift as a token of my gratitude, and hope to see you again soon.